When I first heard about the Forest Service/Bureau of Land Management plan to protect the Rapid Creek Watershed, I let out a whoop of excitement, closely followed by tears of joy and disbelief.

For a few years now, I’ve been working with a team of folks whose goal is just that–to protect the Rapid Creek Watershed, our agriculture, tourism, and recreation economy, and our way of life from threats of mineral exploration and mining.

Discovering that our cause has traction with folks in D.C. was a wonderful surprise.

But, it wasn’t entirely shocking. For months we’d been awaiting word on resolution of the proposed F3 Jenny Gulch gold exploration plan. That plan threatens a beloved recreation area adjacent to Pactola, the watershed’s largest reservoir, and it received thousands of negative public and organizational comments as well as condemnation from Tribes.

As the months ticked by, it became clear that the decision had been kicked upstairs.

If something seems too good to be true, it probably is

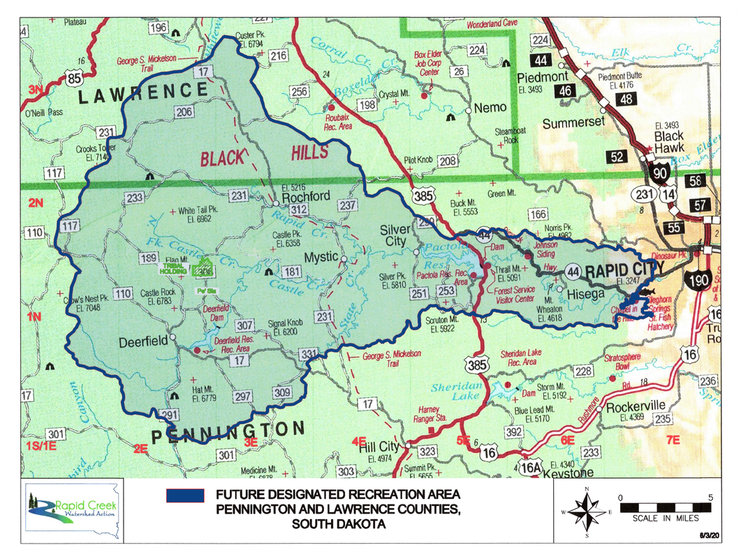

The proposed mineral withdrawal “to protect cultural and natural resources of the Pactola Reservoir–Rapid Creek Watershed, including municipal water for Rapid City and Ellsworth Air Force Base […] from the adverse impacts of minerals exploration and development” was published in the Federal Register on March 21st. It included two columns’ worth of descriptions of areas to be included. All told, the publication claims, it adds up to about 20,574 acres.

Does that seem like a lot? I’m sorry to say that it’s not. By comparison, in January of this year, the Biden Administration announced a mineral withdrawal of over 225,000 acres in the Superior National Forest, adjacent to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

The area of the Rapid Creek Watershed upstream from Rapid City–from its dual headwaters on tributaries of the North Fork of Rapid Creek and tributaries of the South Fork of Castle Creek above Deerfield Reservoir–is approximately 198,000 acres.

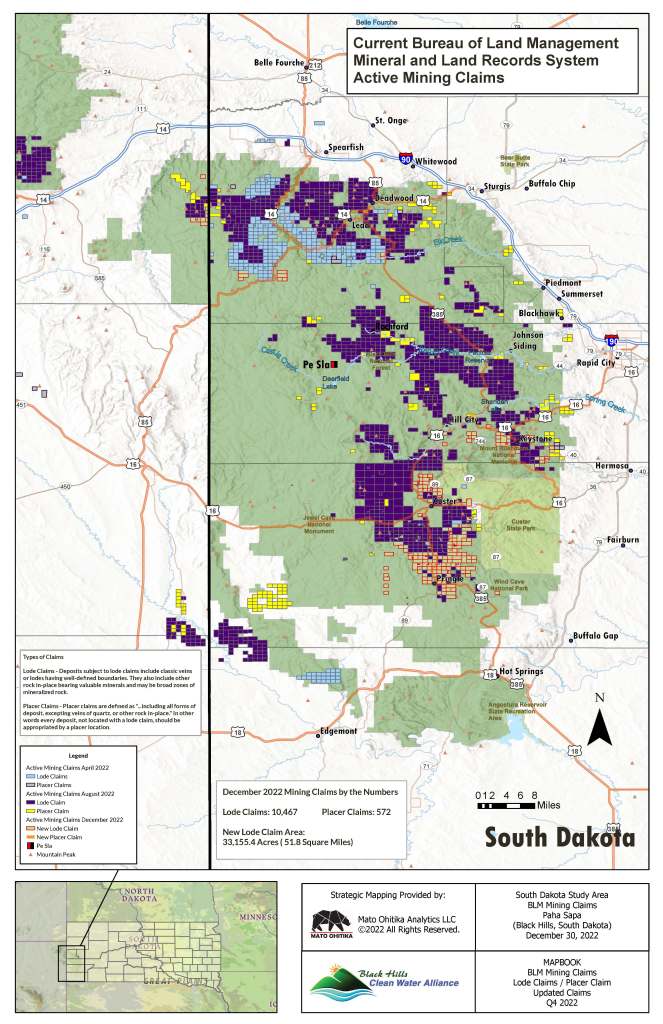

This proposal withdraws from potential mineral exploration and large-scale mining about 10% of a watershed that serves as the primary water supply for an airbase, thousands of rural residents, and the state’s second-largest city.

That’s not a lot of protection.

In fact, it appears that the only areas to be withdrawn from potential exploration and large-scale mining operations are in the immediate Pactola Reservoir area, including portions of Silver City, which happens to be right on the doorstep of F3’s proposed Jenny Gulch gold exploration project.

Silver City is a tiny, isolated, historic mining community. The county road to get there is narrow, winding, and treacherous. A lot of folks in Silver City don’t own the mineral rights underneath their homes, and you’ll see signs to “Protect Rapid Creek” prominently displayed in most every yard.

It’s entirely possible (based on a preliminary map I’ve seen) that while this proposed mineral withdrawal may protect some individual property owners in that community, it may not prohibit a single drill pad in nearby Jenny Gulch.

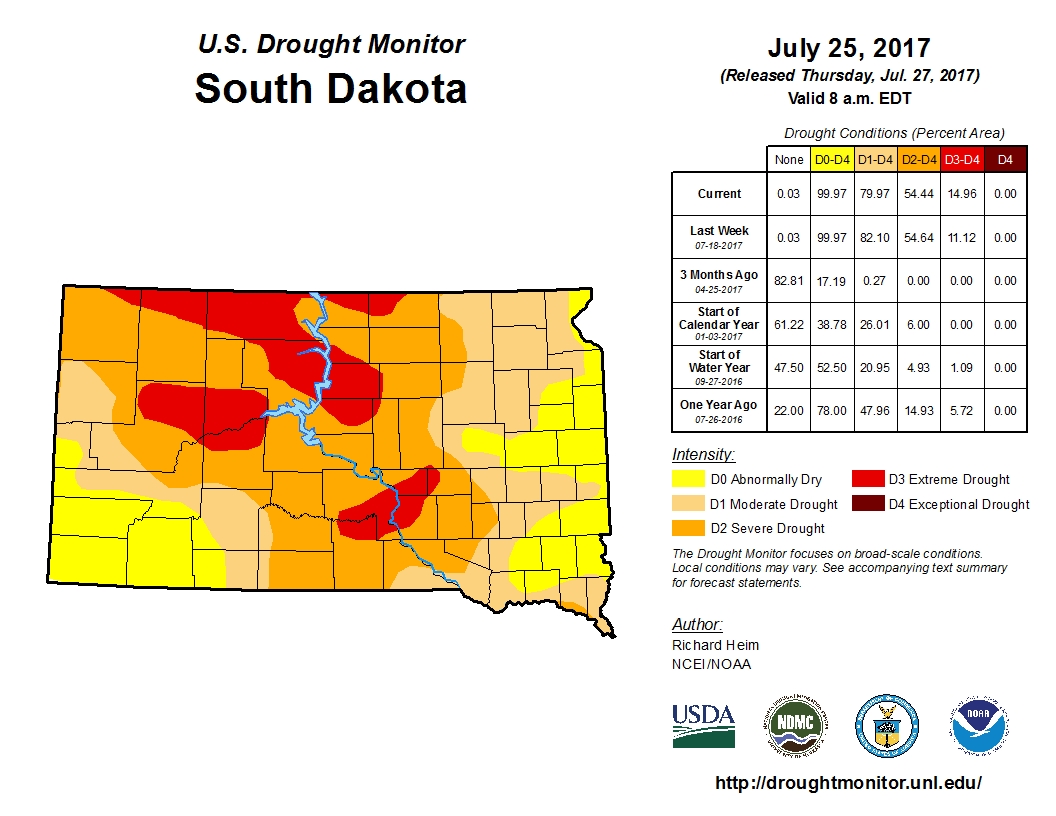

While F3’s Jenny Gulch proposal is on most folks’ radar here in the central Black Hills, it is far from the only potential exploration or mining site on or near Rapid Creek and its tributaries. Mineral Mountain Resources has numerous active claims in the watershed, and has conducted formal exploration near Rochford. Claim activity in the Black Hills has skyrocketed in the past couple of years–in part due to a rise in gold prices, and in part due to the discovery of hard rock lithium deposits.

Protecting watersheds and water supplies means understanding how water flows, both above-ground and below

Thanks to research from U.S. Geological Survey, South Dakota School of Mines (which educates far more environmental engineers than mining engineers these days), state agencies, and others, we’ve got a lot of resources to call on when it comes to understanding the Rapid Creek Watershed. The Black Hills is an incredibly complex area of uplifted geological formations, and we don’t know everything about subsurface fractures, fissures, and flows. But we know a lot.

We don’t need in-depth research to understand some concepts, like the fact that water generally flows downhill and downstream. It’s also easy to grasp that, if we rely on water supplied from a reservoir, we need to protect that reservoir from contamination threats. But, if we only protect the areas around a reservoir without protecting the waterways upstream flowing into that reservoir, we’re not protecting the water supply.

Protecting Pactola alone won’t protect our water supply

Protecting the Rapid Creek Watershed means protections have to extend upstream. If we don’t extend protections upstream, we risk contamination of Deerfield Reservoir, Pactola Reservoir, and everything that flows out of them.

There are plenty of active mining claims downstream from the Reservoir as well. And below Pactola Dam is where it gets (to my mind) even more interesting.

Those outcrops of water-bearing rock formations (aquifers) high in the central Black Hills that feed water into Rapid Creek year-round are also exposed at lower elevations just outside Rapid City limits. And when Rapid Creek flows across those exposed, porous rock formations, a LOT of water (to the tune of a few million gallons a day) gets dumped back into those aquifers.

Those aquifers–the Madison and Minnelusa–are the main formations that Rapid City and Ellsworth Air Force Base (as well as thousands of rural resident and smaller water systems) wells draw from.

There’s no pipeline from Pactola Reservoir to Rapid City or Ellsworth Air Force Base.

Rapid Creek itself is the “pipeline”–and one that supports agricultural activities, timber production, a world class trout fishery, and all manner of other recreational and cultural pursuits all along the way.

Pactola Reservoir “reserves” and controls the flow of Rapid Creek and tributaries and releases it back into Rapid Creek below the dam, replenishing the aquifers we rely on. The City of Rapid City also occasionally pulls surface water directly from Rapid Creek to meet increased demand. When they do that, they’re pulling water out on the west side of the City–below a major aquifer recharge area in Dark Canyon, and far below Pactola Dam.

Contamination upstream from Pactola threatens the Reservoir, as well as the water that flows out of it. Contamination downstream from Pactola threatens not only the surface waters, but the aquifers those municipal wells draw from.

It’s simply false to suggest that municipal water supplies for Rapid City and Ellsworth Air Force Base can be protected by prohibiting exploration and mining only in the area immediately surrounding Pactola Reservoir.

Protecting Pactola is a great start, but it’s nowhere near enough to fulfill the stated goals of the withdrawal. It’s nowhere near enough to protect our water, our agriculture, tourism, national defense, and recreation economy–our way of life.

How to weigh in on the proposed mineral withdrawal

You can comment on the proposed mineral withdrawal via the U.S. Forest Service comment platform HERE. Comments are due by June 19th, 2023 at 11:59pm Mountain Time.

Also plan to attend the joint Forest Service – Bureau of Land Management public meeting on Wednesday, April 26, 2023, 4-8 p.m., Mountain Time (MT), at the Best Western Ramkota Hotel, Conference Hall, 2111 N. LaCrosse Street, Rapid City, South Dakota 57701.

Information regarding the proposed withdrawal will be available at the Black Hills National Forest, Forest Supervisor’s Office, 1019 N. 5th Street, Custer, South Dakota 57730 and at the BLM Montana/Dakotas State Office, 5001 Southgate Drive, Billings, Montana 59101.

Another Path to Protection…

There is more than one path to a mineral withdrawal. The currently-proposed withdrawal is an administrative action which, if approved, will last a maximum of twenty years. It’s important to support it, AND to push for its expansion.

The team at Rapid Creek Watershed Action is working toward a Congressional withdrawal that, if enacted, would protect the entirety of the watershed upstream from Rapid City, and would be permanent unless repealed. You can learn more, and sign the petition for Congressional withdrawal, at rapidcreekwatershed.org.

Photos of the Rapid Creek Watershed in this post include Dark Canyon, Rhoads Fork area, Victoria Creek/Canyon, and Nichols Creek. They were taken by the author.